This guest post was written by Dr. Anna Oehmichen, practising lawyer at Knierim & Krug Rechtsanwälte GbR and a member of our LEAP network from Germany. As with all of our guest posts, the views represented are of the author and may not reflect the views of Fair Trials.

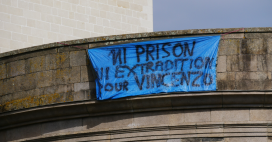

Recent developments in Turkey after the attempted July 15th coup are having far-reaching repercussions in some EU jurisdictions. One example is the German Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein (the Schleswig Court) which recently found that extradition requests from Ankara are currently inadmissible.

Following the attempted coup earlier this summer, the Turkish authorities have arrested and detained thousands of journalists, judges, prosecutors, lawyers and human rights activists suspected to be somehow involved in the insurgency. Emergency provisions, currently in force at least until January next year, are seriously undermining fair trial safeguards and protections against the risk of torture in detention, as recently denounced by an international coalition of civil society organisations, including Fair Trials. A recent report published by Human Rights Watch on 25th October 2016 confirms the torture allegations facilitated by the Emergency Decrees.

To justify its decision, the German Court referred to Turkey’s derogations of fundamental rights of the accused under Art. 15 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR). It based its information not only on the press, but also on other highly reliable sources such as the Foreign Office and the Istanbul Bar. According to Turkey’s internal ministerial decree no. 667, the Schleswig Court explained, police may now arrest a person for up to 30 days without being brought before a judge; the prosecution is authorised to replace the defence counsel of the accused and even prohibit any communication between the accused and his defender. Moreover, after the arrest of thousands of judges and prosecutors, it must be expected that criminal proceedings – already very lengthy – will now take significantly more time, and that prisons’ overpopulation has increased dramatically.

The Court concluded that under these circumstances, the fair trial rights as guaranteed by Art. 6 of the ECHR were officially suspended based on Turkey’s Art. 15 declaration. Additionally, it had to be assumed that present prison conditions facilitate torture, inhuman and other degrading treatment, which is forbidden by Art. 3 ECHR in absolute terms and may not be derogated from even in times of emergency (Art. 15 ECHR).

In a previous decision, another Higher Regional Court in Germany (München) had, only based on press reports, acknowledged the risk that Art. 3 ECHR would be violated in case of an extradition to Turkey due to current prisons’ overcrowding, but considered that this risk could be mitigated by diplomatic assurances from Ankara, and therefore put on hold the pending extradition. Unlike the Munich Court, the Schleswig Court now held that in light of the current situation, it was not even necessary to ask Turkey for diplomatic assurances. The Court found that under the present legal and factual circumstances, i.e. in light of the consequences the derogations under Art. 15 ECHR had already had on the rights of the accused, the Turkish authorities neither would nor could provide an assurance to comply with the fundamental rights of the requested person.

The courage, clarity and absoluteness of this decision are to be strongly welcomed. Whilst it is clear that there may be extradition requests even now from Turkey that are based on “real” (and potentially very serious) criminal cases, including terrorism, and that would generally require cooperation, we must accept that we cannot reach prosecution at all costs, especially not at the expense of the most fundamental rights of the accused. The statement from the Schleswig Court is in line with statements from other European judges, such as Dutch judge Ronny van de Water, who called in July to generally reject any cooperation in criminal matters with Turkey.