Vincenzo Vecchi: when mutual trust and cooperation take precedence over respect for fundamental rights

In 2016, the Italian judicial authorities issued a European arrest warrant (EAW) against Vincenzo Vecchi for the purpose of enforcing a sentence of twelve years and six months’ imprisonment, imposed by an Italian court in 2009 for taking part in a demonstration. This prison sentence was the sum of four sentences imposed for four offences in 2001. One of them, “Devastation and looting” the most severely punished offence (ten years’ imprisonment), was at the heart of the questions submitted by the French Courts to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

The offence of “Devastation and looting” originates from a law implemented under Mussolini’s fascist regime. [1] The law can be used to criminalise the right to demonstration – being at a protest and just in the vicinity of people who commit an offence such as criminal damage can be considered “moral support”, carrying a penalty of between eight- and fifteen-years imprisonment.

In its reference for a preliminary ruling, the French Supreme Court raised two points regarding the double criminality condition. First, the offence of devastation and looting under Italian law referred to multiple acts of destruction and degradation causing a breach of the public peace. French criminal law did not specifically incriminate endangering the public peace through these acts. Second, several of the acts constituting the single offence of devastation and looting did not constitute criminal offences under French law. According to the French Court, because the breach of the public peace appeared to be an essential element for the purposes of the classification of the offence of devastation and looting, and because some of the acts underlying the offence were not unlawful under French law, it raised questions regarding the content of the condition of double criminality.

Moreover, should the above concerns regarding the double criminality principle not be an obstacle to surrender, the question would then arise as to the proportionality of the sentence to that very conduct. It highlighted that the EAW framework decision [2] (the FD) contains no provision allowing the executing judicial authority to refuse to surrender on the ground that the sentence imposed in the issuing Member State appeared disproportionate to the acts for which surrender is sought. It questioned the assumptions made in the FD that the Issuing Court is the best positioned to assess the proportionality of an EAW, insofar as the present case showed that it can become disproportionate at the stage of execution. Here, the conduct described in the EAW would constitute far less serious offences under French law. The referring court therefore asked whether Article 49(3) of the Charter – sentences must be proportionate to the offence – required the executing judicial authority to refuse to execute the EAW.

In its ruling this summer on KL (C168/21), the European court considered that the condition of double criminality is met when the facts underlying the offence – or some of them – for which a person is prosecuted in the issuing state constitute a criminal offence in the executing state, even if the legal definition and the seriousness of these offences vary widely.

Why? Double criminality does not require a perfect match between the (legal) elements – or the definition – of the offences in the issuing and executing states. The Court recalls, what we painfully know too well, that the purpose of the Framework Decision is to help states by facilitating and accelerating criminal prosecution and punishment “with a view to contributing to the achievement of the European Union’s objective of becoming an area of freedom, security and justice” and “to fight against impunity” (although this objective is stated nowhere in the FD).

What do justice, security and freedom mean when state courts have to choose between abdicating their role as guardians of the rule of law and fundamental rights, and the fiction of mutual trust? Especially when there is clear evidence that behind trust, hides persecution and the oppressive use of state powers.

The Court had a choice. It could have stretched the grounds for refusal to surrender as it has done in the past.[3] Alternatively, it could have decided that the FD, a relatively old instrument and notoriously problematic in its enforcement,[4] does not comply with the Charter and other human rights obligations because it leaves the executing courts too limited powers to prevent fundamental rights violations in the issuing state by refusing to surrender. It could have decided that the FD goes beyond what is necessary to achieve its objective (see above) and as such breaches another sacrosanct principle: the proportionality of EU law.[5]

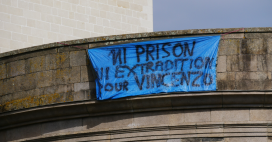

When states’ obligations regarding one another clash with their obligations to respect the fundamental rights of people in their jurisdiction (as in this case, Mr Vecchi), what should take precedence? Whose trust should prevail? What is clear is that the trust that people have in European justice will only continue to erode so long as mutual trust and cooperation take precedence over respect for fundamental rights.

[1] « Dans l’affaire Vincenzo Vecchi, la Cour de cassation est notre dernier rempart pour la défense des libertés publiques », Le Monde, 2022.

[3] See e.g., C-404/15 – Aranyosi and Căldăraru

[4] Reinforcing procedural safeguards and fundamental rights in European Arrest Warrant proceedings, Fair Trials, 2021.

[5] Treaty on European Union, Article 5

See also Vincenzo Vecchi, enjeu malgré lui de la Justice européenne, Véronique Lamquin in Le Soir, 2022 and Comité de soutien à Vincenzo Vecchi.