On this page

“Call them crazy”: Criminalisation of activists undermines rule of law in the EU

The Dutch police continue to disregard the rule of law to criminalise the pacifist activist Frank van der Linde. In recent years, his personal data has been sent to Europol, he has been labelled a terrorist, and police have suggested he be referred to a psychiatric facility. Far from an isolated case, van der Linde’s story shows just how far police in Europe will go to criminalise the right to protest and stifle political dissent.

Van der Linde is a left-wing activist involved in actions against racism, discrimination, climate change, animal cruelty, homelessness, and other social injustices. In early February 2023, he was told by a whistle-blower in the Dutch police that he was described in his police file as a ‘multiple offender who could benefit from being referred to a psychiatric facility’. He has asked the police to rectify this baseless classification.

In recent years, van der Linde has come into contact with police due to his participation in peaceful public protests, demonstrations, sit-ins, or even for tweeting. He has been detained at the police station for varying lengths of time, ranging from a few hours to overnight detention. However, he always contested his arrests in court, and either judges have repeatedly acquitted him or the prosecutor has dropped the charges, agreeing that the police used disproportionate measures.

His case is not isolated. Nine years ago, another individual was profiled in the same way. While van der Linde is not the repeated offender the police portray him to be, the opposite might be said of the police, given the number of times their actions against activists have been overturned by judges.

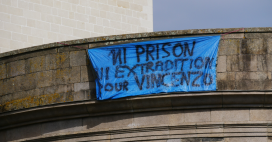

Similar cases have been seen across the EU. Last month, 88 organisations stated that the “police have crossed the line” and called on Spain to stop illegal policing against activists, following recent revelations about undercover police officers infiltrating social movements by using sexual and intimate relationships as cover. The police tactics in those cases reflect the deception and abuse employed by British police in undercover operations against activist groups going back decades.

“Terrorism” is a broad term.

It is not unprecedented for van der Linde to be mischaracterised by the police. In 2018, the Dutch police sent his personal information to their German counterparts and Europol, labelling him a potential terrorist. This came as a surprise since van der Linde has only been convicted for breaking the window of a building so that migrants would not have to sleep in the street.

Recently, the police sent van der Linde a letter that is remarkable for its complete disregard for the rule of law. It justified sharing the information with Europol and German police by indicating that: “There was no other choice… than to choose the field ‘terrorism’. The other options relate more to forms of serious crime, such as organised crime, drug trafficking, money laundering, etc.” The Europol regulation only allows the sharing of data through the agency’s information exchange system (SIENA) for cross-border investigations that concern sufficiently serious crimes.

The way in which the Dutch police stretched the definition of terrorism to exchange data via the Europol system does not come as a surprise in the context of counter-terrorism discussions in the EU. The German presidency of the Council of the EU drafted conclusions in 2020 calling for member states to adopt a common approach on “potential terrorists”. The draft conclusions left a large margin of appreciation for member states to qualify someone as such, but reports published by Europol leave no doubt about some of the targets. As noted by Statewatch in 2020:

“The 2020 edition [of the annual report of Europol indicated that] in 2019: ‘The number of arrests on suspicion of left-wing or anarchist terrorism in 2019 more than tripled, compared to previous years.’ However, it goes on to say that 71 of 111 arrests ‘were linked to violent demonstrations and confrontations with security forces’ – a public order issue, perhaps, but not quite terrorism.”

Data failures

Europol has been consistently denounced for its handling of personal data. Last year the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), admonished the police agency for the unlawful processing of massive datasets of persons not suspected of any crimes. As described in a recent report by Statewatch, new laws further empower the police agency whilst removing safeguards for individuals.

The EDPS has also requested that the Court of Justice of the EU annul two provisions of the newly adopted Europol Regulation. The two provisions have an impact on data processing operations carried out in the past by Europol and retroactively legalise Europol’s practice of processing large volumes of personal data on individuals with no established link to any criminal activity.

Wojciech Wiewiórowski, the EDPS, said that by adopting the Europol Regulation, European legislators “retroactively deprive individuals of the safeguards that the EDPS enforced.” He further warned that it could establish a worrying precedent undermining the rule of law and the independence of the supervisory authority.

In van der Linde’s case, the Dutch police argued that “the term ‘terrorism’ is a broad term” and Europol’s report suggest the agency is thinks along the same lines. Frank van der Linde’s case is just the tip of the iceberg.

Who knows how many activists’ data is being shared with the EU’s police agency under the justification of ‘terrorism’?

‘On paper, government agencies should be transparent, but in reality, it’s almost impossible to find out what data is stored.’

Gaining access to your data is no walk in the park, as van der Linde has found out in recent years. His inability to access his personal data is yet another illustration of the lack of access to effective remedy in the EU – something that should be guaranteed under Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Two and a half years ago, van der Linde complained to the EDPS that Europol had not given him access to his personal data. The EDPS ruled in his favour in September 2022, denouncing Europol for trying to delete the data rather than hand it over to the activist. However, he still hasn’t had access to any of the information about him stored by Europol.

Since he submitted his first access to information request about his file in the Netherlands, he has been to court 70 times over the last five years. “It’s exhausting to go back and forth to different government agencies to find out what data is stored about me,” said Frank van der Linde. “What do they want to hide? On paper, government agencies should be transparent, but in reality, it’s almost impossible to find out what data is stored.”

To guarantee that the police are not hiding any further data, van der Linde will ask the Court of Amsterdam, during a public hearing on the 30th of March, to request an independent external institution to conduct an audit of the police database. It his arguments are accepted, it would be the first time a court has ordered an investigation into a police database to protect an individual’s right to data protection. It could be a stepping stone for better law enforcement accountability in Europe.

But as a judge in the Netherlands already noted, it matters little if data is removed, as the “information whose source has been removed or even destroyed may still live on in other ways, such as in the minds of employees and among agencies to whom that information was provided.”

A police officer that believes a person is a risk to security may well just create a new file containing the same information. Even through the right to rectification of inaccurate data can enable a person, after a cumbersome process, to rectify information about them, a police officer opinion cannot be rectified.

For example, the fact that a police officer has been recorded in a public file saying that someone should be referred to a psychiatric facility for treatment is not rectifiable. In the Netherlands, if that opinion does not result in any kind of administrative measure, the court considers it to be personal data belonging to the officer that expressed this opinion. While this may make legal sense, even though it is contested by the doctrine, it leaves individuals with a severe problem in accessing an effective remedy against the police.

Mr. van der Linde as an activist has been on the front line of the fight against police surveillance. It should however be noted that he is in a privileged position to keep pursuing what has been a long battle to defend his fundamental rights. Most people who are targeted by police surveillance are not. Many have less access to legal aid or a support network, and may risk being deported upon encounters with police.

If EU states are really committed to the rule of law, they must guarantee that an independent oversight mechanism can effectively investigate and prevent future violations.